Animal testing: Could it ever be banned completely?

Animals will continue to be used for testing medical products until there is a viable replacement.

Photo Credit (Getty Images: Rklfoto)

By Bianca Nogrady

There’s an uncomfortable truth to modern medicine.That drug you take for your high blood pressure, the vaccine to prevent infectious disease,

the pill to avoid pregnancy, the medical ointment for your skin condition, or even the pacemaker keeping your arrhythmia in check — all of those and more have, at one time, been tested on a live animal.

Between the testing of a new chemical compound on cell cultures in a laboratory and the first time that compound is given to a live human, it will almost certainly be administered to mice, rats, rabbits and perhaps even a non-human primate. Read More

A New Culture of Openness in Animal Research

Photo credit Speaking of Research

By Sarah Elkin

Animal research has been credited with improving human health and leading to many medical breakthroughs. However, animal research still remains a controversial topic, with many animal rights groups believing that animal research is wasteful and pointless. One way to improve the public opinion of animal research is through education and openness. Openness can be achieved by showing the public what an animal research facility looks like and what research takes place there, in addition to discussing how that research affects human health.

In order to address the goal of transparency and openness in animal research, 72 organizations involved with bioscience in the United Kingdom (UK) launched the Concordat on Openness in Animal Research. Currently, over 100 UK organizations have signed the Concordat and pledged to “be clear about when, how and why [they] use animals in research”, “enhance [their] communications with the media and the public about [their] research using animals”, “be proactive in providing opportunities for the public to find out about research using animals”, and “report on progress annually and share [their] experiences”. The Concordat, and the new environment of openness it seeks to encourage, has led many institutions to become more open to the media. Read More.

Similarities Unite Three Distinct Gene Mutations Of Treacher Collins Syndrome

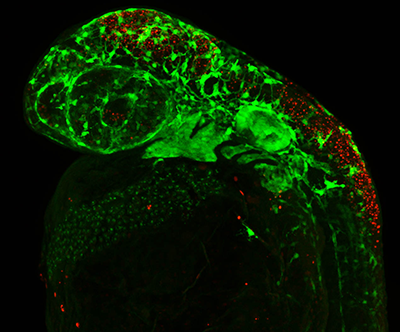

Cell death (labeled in red) within the neural crest cell progenitor population results in a reduced population of neural crest cells (labeled in green) in a polr1d mutant zebrafish embryo.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Trainor Lab.

Scientists at the Stowers Institute for Medical Research have reported a detailed description of how function-impairing mutations in polr1c and polr1d genes cause Treacher Collins syndrome (TCS), a rare congenital craniofacial development disorder that affects an estimated 1 in 50,000 live births.

Collectively the results of the study, published in the current issue of PLoS Genetics, reveal that a unifying cellular and biochemical mechanism underlies the etiology and pathogenesis of TCS and its possible prevention, irrespective of the causative gene mutation. Read More.

Published by Stowers Institute For Medical Research July 26, 2016

Reopening avenues for attacking ALS

Photo courtesy of Dan Mordes, Eggan lab, Harvard Stem Cell Institute

Harvard Stem Cell Institute (HSCI) researchers at Harvard University and the Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT have found evidence that bone marrow transplantation may one day be beneficial to a subset of patients suffering from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), a fatal neurodegenerative disorder more commonly known as Lou Gehrig’s disease.

In the photo of the murine spleen shown, lymphoid tissue (purple) is responsible for launching an immune response to blood-born antigens, while red pulp (pink) filters the blood. Mutations in the C9ORF72 gene, the most common mutation found in ALS patients, can inflame lymphoid tissue and contribute to immune system dysfunction.

ALS destroys the neurons connecting the brain and spinal cord to muscles throughout the body. As those neurons die, patients progressively lose the ability to move, speak, eat, and breathe. Read More.

Use it or Lose it: Visual Activity Regenerates Neural Connections Between Eye and Brain

Regenerating mouse retinal ganglion cell axons (magenta and green) extending from site of optic nerve injury (left). Photo courtesy of Andrew D. Huberman.

NIH-funded mouse study is the first to show that visual stimulation helps re-wire the visual system and partially restores sight.

A study in mice funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) shows for the first time that high-contrast visual stimulation can help damaged retinal neurons regrow optic nerve fibers, otherwise known as retinal ganglion cell axons. In combination with chemically induced neural stimulation, axons grew further than in strategies tried previously. Treated mice partially regained visual function. The study also demonstrates that adult regenerated central nervous system (CNS) axons are capable of navigating to correct targets in the brain. The research was funded through the National Eye Institute (NEI), a part of NIH. Read More.

Do Politics Trump Chimpanzee Well-being? Questions Raised About Deaths of US Research Chimpanzees at Federally-Funded Sanctuary

Photo Credit: Kathy West

A number of countries have ended some types of research with chimpanzees over the past decades. For example, the US National Institutes of Health announced in November 2015 that it would no longer support many types of chimpanzee research. In Europe, the fate of former research chimpanzees has depended upon a mix of private wildlife parks and zoos for the animals’ care and management. The outcomes in term of chimpanzee health and survival remain relatively unknown. Read More.

Flies sleep just like us. And they might help give humans a good night’s rest

Sleep is a mystery. It’s essential — without enough sleep, we die — and yet scientists still aren’t sure why we need it.But the how of sleep is just as intriguing as the why.

Sleep is a mystery. It’s essential — without enough sleep, we die — and yet scientists still aren’t sure why we need it.But the how of sleep is just as intriguing as the why.

Amita Sehgal, a sleep researcher at the University of Pennsylvania, has discovered some of the key genes that control our 24-hour circadian cycle, making us fall asleep at night and rise again in the morning. Sehgal didn’t find these genes in people, however. She found them in flies. Read More.

Monkey study shows Zika infection prolonged in pregnancy

University of Wisconsin–Madison researchers studying monkeys have shown that one infection with Zika virus protects against future infection, though pregnancy may drastically prolong the time the virus stays in the body.

The researchers, led by UW–Madison pathology Professor David O’Connor, published a study today (June 28, 2016) in the journal Nature Communications describing their work establishing rhesus macaque monkeys at the Wisconsin National Primate Research Center as a model for studying the way Zika virus infections may progress in people. Read More

Published by University of Wisconsin – Madison June 28, 2016

HIV Vaccine Developed Through Primate Centers Collaboration

Moving towards human clinical trials

Moving towards human clinical trials

Over the past 6 years, Drs. Peter Barry and Alice Tarantal, California National Primate Research Center (CNPRC) at UC Davis, have been collaborating with Dr. Louis Picker at Oregon Health Science University (OHSU)–Oregon NPRC to develop and test a vaccine and potential cure for HIV. OHSU is now recruiting volunteers to be part of the first human trials for this exciting new development in the prevention and treatment of HIV. Read More.

Published by California National Primate Research Center – UC Davis June 10, 2016

We mightn’t like it, but there are ethical reasons to use animals in medical research

The media regularly report impressive medical advances. However, in most cases, there is a reluctance by scientists, the universities, or research institutions they work for, and the media to mention animals used in that research, let alone non-human primates. Such omission misleads the public and works against long-term sustainability of a very important means of advancing knowledge about health and disease.

The media regularly report impressive medical advances. However, in most cases, there is a reluctance by scientists, the universities, or research institutions they work for, and the media to mention animals used in that research, let alone non-human primates. Such omission misleads the public and works against long-term sustainability of a very important means of advancing knowledge about health and disease.

Consider the recent report by Ali Rezai and colleagues, in the journal Nature, of a patient with quadriplegia who was able to use his hands by just thinking about the action. The signals in the brain recorded by implanted electrodes were analysed and fed into the muscles of the arm to activate the hand directly. Read More.